Amelia Hirth-Meyer

“What was a woman to do with a new baby and a nine-year old son when she had also just lost the support of her husband and father-in-law?”

Ellington, Connecticut.

The vision of an adoring Madonna reminiscent of Renaissance art is not what I recall when I think of my paternal grandmother. No, not my Grandma Meyer. Born in Germany, she came to the United States as a young child but maintained a staunch German demeanor throughout the life she lived in the little picture-perfect New England town of Ellington, Connecticut. That is where I came to experience her as a child of nine or ten myself when my siblings and I stayed with her during summer vacation. It was a welcome respite from the summer heat in Hartford where I grew up in a poor family of seven children. The bucolic countryside provided fields for half-naked children to play in during cool afternoon showers.

My siblings and I felt Grandma mean and miserly, though. She had a switch close at hand to correct any misbehavior she perceived in her charges though it was usually my brothers who felt its sting. I was always mindful of avoiding her disapproval.

Yes, we feared Grandma Meyer and this fear intensified when my older brother, Karl, and I were dispatched to the woods to pick berries for the pies she baked in her large meticulously organized kitchen. Despite the promise of sweet-smelling confections, I dreaded those daily excursions knowing we were sure to encounter a large black snake curled up under those threatening sticker bushes. That fear of snakes was so intense I eventually seemed to sense that reptilian presence before I even saw them, and that fear of snakes followed me into adulthood.

We children thought Grandma Meyer stingy too. I do not recall ever receiving a gift from her though she seemed to have plenty of money. I do recall a time Karl, and I spied on her while she counted her money in a chest she kept hidden in the attic. There seemed to be lots of cash that we could see from our cramped hiding place behind the tall cedar wardrobe. She never seemed to spend any of her money though. Grandma regularly gave my father weekly receipts for the food she purchased for us kids. She even included her coffee in the amount she expected to receive for our care. I must admit to remembering a softening in this usually strict image of my grandmother when she drew my crying infant brother to her ample breasts and rocked him gently to soothe him to sleep. Babies seemed to disappear peacefully into her ample bosom but none of us older children ever felt that comforting touch.

“Why is Grandma so mean?” we older children often asked each other.

I grew up not knowing, and it was not until I was a grandmother myself that I discovered facts about her that nobody in my family talked about. In fact, nobody in my family ever talked about anything except for what was necessary to get things done. Family history and feelings were never discussed. Not until my own children were grown, did I realize that I too was guilty of not passing family history on to my children and grandchildren. To my defense, however, I had little to pass on because I was given little.

That is when Ancestry.com afforded me an opportunity for a remedy and I set out to develop history books for my family. My son and daughter were delighted to get those books for Christmas one year which encouraged me to learn more about the family of origin I hardly knew.

I learned that most of my father’s family sailed from Germany in the late 1800’s at a time when immigrants were expected to assimilate into American society. Many of my ancestors settled in Rockville, Connecticut which had many textile mills that provided them with good jobs. They apparently worked hard and began to thrive. As children grew to adulthood, they could also rely on finding work in the mills. Many were able to buy homes with land that they could farm. The family began to prosper in its adopted country as did many Eastern European immigrants.

I learned that my paternal grandmother, Amelia Meyer, was born Amelia Seidel March 7, 1892 in Brandenburg, Germany, the daughter of Daniel and Mary Lastec. She came to America with her parents in1893 along with two brothers and three sisters.

As I discovered more about Grandma Meyer’s life, I came to understand why she was so rigid and hard to get close to. Apparently, her father, Daniel, died of heart disease at 48 years of age in 1900 when she was sixteen years old. In his will which I found in Ancestry.com, there is a petition for guardianship for Amelia Seidel. Her mother’s residence was listed as “unknown” and states “said parent and natural guardian aforesaid, is an unfit person to have the care and custody of said minor.” I could find no record of siblings at the time the will was written.

The only sibling that I ever met was Aunt Wanda. She was a hairstylist who lived in Chinatown in New York City after she married Ong Yee, a Chinese man who died long before I was born. I knew Aunt Wanda only slightly and never met her only son, Robert.

Amelia married my grandfather, Emil Gottlieb Hirth in 1908 when she was 16 years old, obviously soon after her father’s death. They had a son, Richard, born in 1909 and then my father, Edmond, was born in 1918. It is possible that she became pregnant in the intervening years because the Hirths usually had large families. Perhaps there were other babies lost to Emil and Amelia.

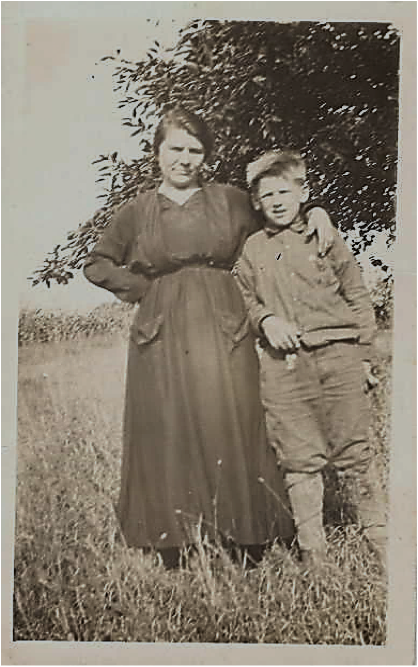

Grandma Meyer and son, Edmond “Edwin.”

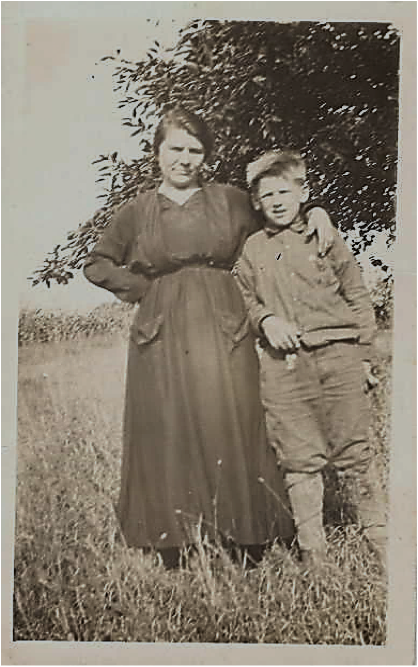

Grandma Meyer and son, Richard

The year 1918 was obviously a traumatic year for my grandmother and the Hirth family, as well as the rest of the United States. Tensions had been brewing for years throughout Europe. In 1914, following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the world was thrust into the carnage and destruction of trench warfare that consumed the political, military, human, and financial resources of major European alliances for the next four years.

My family and many other families experienced many hardships that would test their fortitude, particularly 1918 when the United States entered World War I, the “War to end all wars.” More than nine million soldiers were killed and twenty-one million were wounded in the war. Civilian casualties numbered close to ten million. Though Germany and France were the nations most affected by the war, each of which sent eighty percent of their male population between fifteen and forty-nine into battle, the United States suffered dearly as well.

Though he had been registered for the military in 1917 in what was called the old man’s draft, my great grandfather, Frederick Hirth, never got to enlist. He died May 26, 1918, just five months after my father, Edmond’s, birth, January 27, 1918.

My Grandfather, Emil, was drafted September 12 of 1918 during a major draft effort intended to bring an end to the war. He died of the Spanish flu and pneumonia at the local Rockville Hospital on October 16, 1918. He was only thirty-four years of age. I consider it a blessing that he died in a hospital and was therefore spared the horrid fate of draftees sent to army camps that were overcrowded with sick and dying soldiers, victims of what was then world’s worst pandemic in history.

What was a woman to do with a new baby and a nine-year old son when she had also just lost the support of her husband and father-in-law? Well, Grandma Meyer went to work. From then on, she spent the rest of her life working hard to avoid the “Poor Houses” which struck fear in the population during that time.

It was this first global war that helped spread the Spanish flu. This disease killed an estimated twenty to fifty million people worldwide. Few countries were immune and though it wasn’t isolated to one place, it became known around the world as the Spanish flu because Spain was hit particularly hard by the disease and was not subject to news blackouts like the rest of the European countries.

The population hit hardest by this killer virus was previously healthy young people. The military was particularly impacted as servicemen were crowded together in barracks. Troops on ship and trains spread the virus throughout the world. Forty percent of the U.S. Navy was hit with the flu and thirty-six percent of the Army was affected. The Spanish flu killed more military personnel than were killed in combat.

Massive social upheaval also resulted from the war and the pandemic. Millions of women entered the workforce to support men who went to war or replace those who didn’t return. Whole families were wiped out by the flu, leaving countless widows and orphans. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed, and bodies piled up. Many people had to dig graves for family members and mass graves were also used to bury the dead.

This series of tragic events had a huge impact on my grandmother, my father, his brother, and untimely me and my siblings though I have little knowledge of what happened to them immediately following the war.

I did learn that my grandmother sent my father to live with her sister, Wanda, and her husband Ong Yee in New York’s Chinatown when he was only eighteen-months old. That may have been when his name changed from Edmond to Edwin, probably easier for a Chinese uncle to pronounce. I do not know how long he lived with them, but I do know he and his mother were estranged for many years when he became an adult.Grandma Hirth apparently remarried, to a man named August Meyer several years later. That is why I knew her as Grandma Meyer. I never met August. Apparently, he died when my father was eighteen years old.

Because my father and grandmother were estranged, I did not get to meet Grandma Meyer until my siblings and I started spending summer’s with her at her house in Ellington. I got to know her a little better when my family moved to Ellington in 1957, but I never did know her very well. Now, some fifty years after her death in 1970, with more knowledge of the overwhelming trauma she experienced in her life, I have more understanding of why she was so unapproachable and ungiving.

Contributed by Barbara Skelly, Granddaughter of Amelia Hirth-Meyer.