Mary Wingard Yoder

“Why is he crying?” wondered my mother, who was six-years-old at the time.

Goshen, Indiana and Shipshewana, Indiana

He came back into the house, went to a chair in the living room, put his elbows on his knees, his head in his hands, and sobbed. “Why is he crying?” wondered my mother, who was six-years-old at the time. “The funeral’s over.”

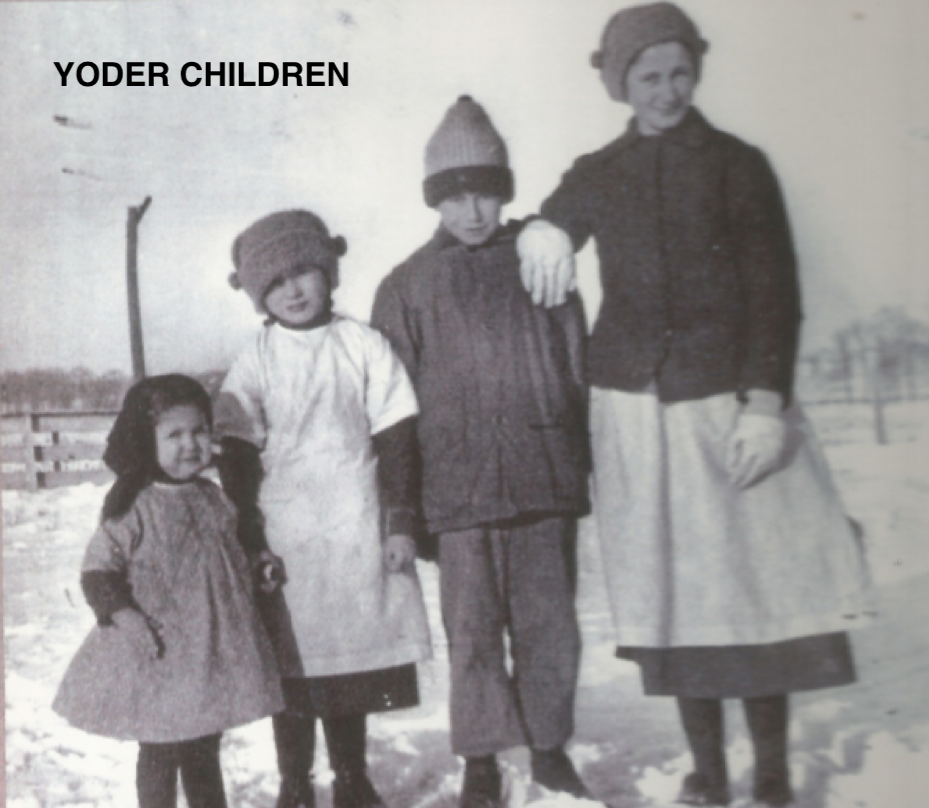

Her father, Henry Yoder, a lanky man who was thirty five years old, and over six feet tall, was left with four children, ranging in age from one to eleven. Two days after Christmas, on December 27, 1918, Mary Wingard Yoder, ill with the flu, gave birth to a daughter, who died the same day. Mary herself succumbed the next day. “No one who was pregnant and had the flu that year lived,” my mother told me years later, which, while not factually true, was their lived experience.

I was raised in a Mennonite community in Indiana. My grandmother and grandfather were Amish- Mennonite, but our step-grandmother was Mennonite, and she raised the children Mennonite after the death of her first husband. Many of my relatives on both my grandfather’s and grandmother’s side remain Amish. Anyone reading this story who is Mennonite will recognize the last names as “ethnic” Mennonite. I moved to Philadelphia 50 years ago, in 1970, and married an Italian here.

Growing up, I was always afraid when a flu was going around, not understanding that this flu was like no other, before or since. It killed people in the prime of their lives. I knew that victims often died within hours or days of exhibiting symptoms due to a secondary bacterial infection, and that the cause was attributed to pneumonia. What I learned much later was the theory that people’s immune systems went into high gear, which flooded the lungs and was thought to be the actual cause of death.

Celestia and Henry Yoder in their wedding portrait

Surviving Yoder children

The 1918 Flu Pandemic left a lasting legacy on our entire family, even affecting the fourth generation. My grandfather hired a housekeeper who didn’t stay, and then another one, Celestia, who was twenty- two at the time, and fourteen years younger than Henry. They married in 1920. A year later, Henry was “kicked by a horse” (it is always stated this way), which fractured his skull. I was told he developed septicemia. He died after several days, leaving his young widow with three step-daughters and a step-son. The children helped on the farm by taking care of the chickens and cows and tending the vegetable garden. When they were older, they worked away from home in the summers. Their step-mother added to the income by becoming a home health aide. While Celestia had offers from people to take one child or another, she kept the children together. Henry asked before his death “You will keep Carrie, won’t you?” Carrie was then four-years-old. Celestia refused to remarry until Carrie was seventeen and could move in with her oldest sister and her husband. For this, the children, and we, the descendants, are grateful. Having lost both of their parents, they only had each other. Carrie died during the current COVID19 epidemic on June 27, 2020, due to gastrointestinal bleeding. She was one hundred three years old.

Story contributed by Ruth Marino, Granddaughter of Mary Wingard Yoder and Henry Yoder